Molecular Modeling 1

How do you model something?

Let’s talk about molecular modeling from both the chemistry and mathematic standpoints. When you want to model something, what do you need?

- An equation or objective function that describes the system of interest

- Parameters and variables that quantify the relevant inputs

- Consequently, you need to determine what are the relevant properties

- A robust, informed way to develop these parameters

- Assumptions are always built into a model

- This is always important if you’re going to understand the model’s limitations

- A method to sample, simulate, or gather data via this model

- Some sort of output, measurable, or result that can be computed from the model

How do you model a molecule?

In molecular modeling, the equations or objective functions of interest are those that describe the potential energy of a chemical system. This is known as a potential function or force field, and it is a function of a system’s coordinates.

Of what are you measuring the energy?

Back to general chemistry, molecules are composed of atoms. Atoms are composed of electrons, protons, and neutrons. Atoms have bonded interactions and nonbonded interactions. It is these interactions whose energy we try to quantify and describe. There are two approaches to quantifying the energy and describing a chemical system

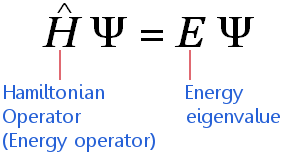

Quantum mechanics (QM) descriptions

image from https://www.chemicool.com/images/schrodinger-equation-time-ind-annotated.png

image from https://www.chemicool.com/images/schrodinger-equation-time-ind-annotated.png

The underlying equation in QM is Schrodinger’s equation. Molecules are modeled using wavefunctions, which are computed via the atomic orbitals in which each electron participates. For a modeler, the inputs are the ways we describe the orbitals. This level of detail ranges from highly-detailed ab initio methods, to semi-empirical methods, to lower-detailed density functional theory (DFT). From our description of atomic orbitals, we can obtain molecular orbitals and wavefunctions.

After modeling these wave functions, we try to identify the molecular coordinates and geometries that minimize the energy of our system. Minimizing the energy or optimizing the geometry of a system is VERY computationally expensive. On current supercomputers, we can maybe study up to 100s of atoms. With a detailed ab initio method, you’re very accurate, but the calculations are extremely expensive. With a less-detailed DFT method, you’re less accurate but the calculations are less expensive. As in all modeling, there is a tradeoff between computational expense and accuracy.

Once optimized, we can make observations about electronic and thermodynamic properties of our system. Depending on the method, we can also study some reaction mechanisms.

In general, quantum mechanical models are accurate and desirable because the only necessary inputs are how you want to describe the electrons, and the resultant chemistry and physics fall out via simulation. However, the fundamental limitation is the computational expense that restricts these methods to small systems.

Molecular mechanics (MM) descriptions

Molecular mechanics utilizes Newtonian mechanics to describe chemistry, sacrificing the detail of quantum-level descriptions in favor computational efficiency. This allows us to study upwards of one million atoms (your mileage may vary, but at time of writing, specialized hardware and algorithms have just begun to hit this astounding feat). More typically, system sizes are on the order of 10,000 to 100,000 atoms, with length scales on the order of 10s to 100s of nanometers, with time scales on the order of nanoseconds to microseconds (and milliseconds if you have the specialized hardware).

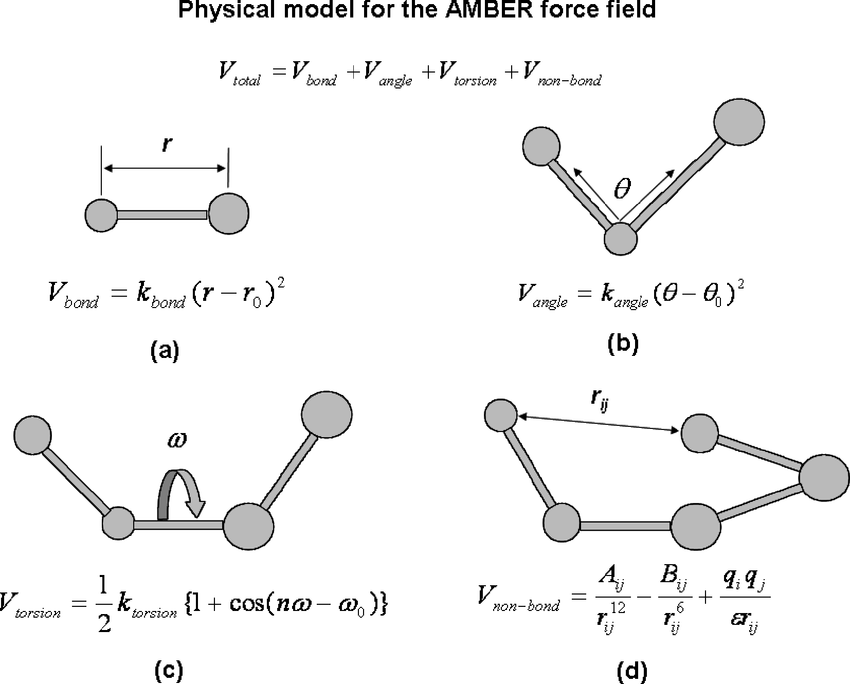

MM models are notably different from QM models in that MM models are more involved in describing bonded and nonbonded interactions. In MM, you specify a lot of the chemical behavior via many simpler equations. See below for an example potential energy function or force field (the Amber FF).

image from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ling-Hong_Hung/publication/5773728/figure/fig1/AS:340704250351617@1458241631445/The-physical-models-for-the-AMBER-molecular-mechanics-force-field-Atoms-and-bonds-are.png

image from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ling-Hong_Hung/publication/5773728/figure/fig1/AS:340704250351617@1458241631445/The-physical-models-for-the-AMBER-molecular-mechanics-force-field-Atoms-and-bonds-are.png

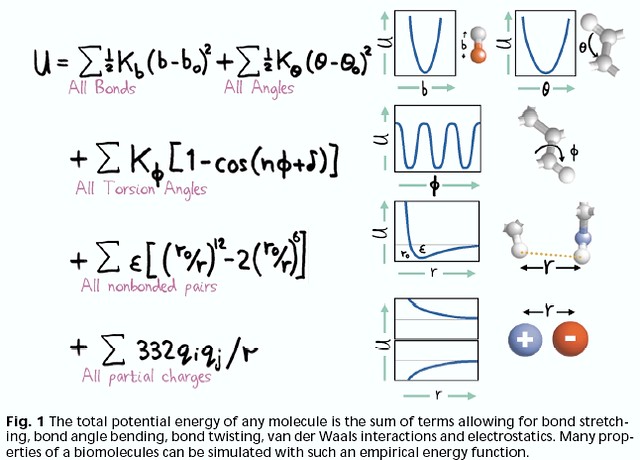

For every bond, angle, dihedral, or non-bonded pair in your system, there is an equation that describes the energy as a function of distance or angle. As you can see, the equations might be something you learned from intro physics courses - harmonic springs, cosine series, coulomb’s law. It’s actually quite remarkable that these very basic equations not only do a pretty good job describing our system, but they actually fall out of the theory and approximations (see below for some example energetic profiles).

image from https://live.staticflickr.com/2/1608614_5ae09db3ec_z.jpg

image from https://live.staticflickr.com/2/1608614_5ae09db3ec_z.jpg

Armed with these force fields, we can perform simulations and obtain a plethora of properties:

- Transport properties (diffusion, viscosity, heat transfer, permeability, conductivity, friction)

- Thermodynamic properties (free energies, heat capacities, density, activity coefficients, heats of vaporization, vapor pressure, contact angles, surface tensions)

- Structural properties (crystallographic, packing, phase behavior)

- Protein folding, membrane signaling, membrane transport

- Metal-organic frameworks and zeolites and their loading capacity

- Relative free energies to compare chemical states and drug binding affinities

Even though MM methods broaden the scope of things we can computationally study, there are still many, many natural phenomena MM methods still cannot attain.

- Many biological phenomena occur on length and time scales just out of reach, but the computational resources are always growing.

- Bulk material properties and crack propagation are things amenable to more finite element methods.

Furthermore, the quality of the computational result is dependent on the quality of the model. Garbage in, garbage out.

Concluding remarks

Molecular modeling is much like any other sort of modeling, you have a system of interest and you want to describe the parameters, properties, features of interest via some sort of equation. The choice of model (QM to MM) will depend on the problem you are trying to solve. Accuracy vs computational expense is a neverending battle.

The bread and butter of my PhD research utilizes molecular modeling via molecular mechanics methods. I’ll be back again to discuss the computational techniques within molecular mechanics, sampling/simulation with these models, and some of the analysis/quantities we like to report.