Technical Debt

Published:

Technical debt is an ongoing, ever-pressing issue to any large, collaborative code base. If left unaddressed, technical debt can seriously cripple productivity.

Contextualizing the issue in academia

You’re a STEM graduate student or young professor in the 70s or 80s. Coding standards, software practices, continuous integration, unit tests, and modularity haven’t been popularized. The codes you wrote were very long scripts tailored to your particular problem. Your code was bad, and the only person who could use your code was you.

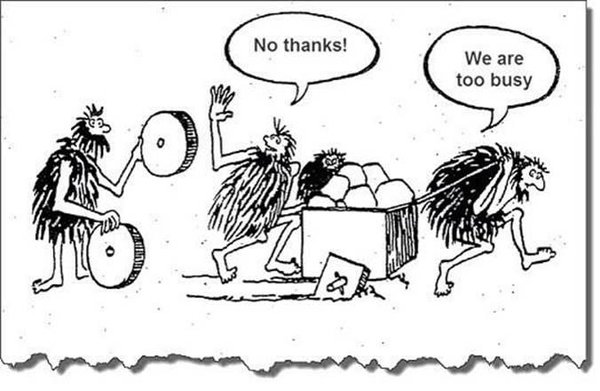

You’ve probably tried to share your code with a collaborator, mentee, or student, but it’s incredibly hard for him/her to navigate and use your code. Maybe you could spend some time to re-design and re-factor for extensibility, but time is publications is money in the life of an academic. You’ll do it later.

Years pass and your messy code has grown from 100 lines of hard-to-understand, poorly-tested software to thousands of lines of mess. At this point, if you wanted to re-factor, it would be a significant overhaul that would require considerable amounts of time, energy, maybe money that would detract from publishing. Uh-oh. On top of that, you’re far enough in your career that you’re not the one writing the code anymore, so you’ll need some help.

Problems that arise

For starters, messy code is harder to learn than well-organized, documented code. If you’ve ever been thrown in the deep-end of a codebase without a guide, you’re left floundering for quite a long time. If it was a better codebase, you’d still struggle, but way less.

In the grand scheme of “good science”, your methods and techniques need to be reproducible by others. This could be as simple as re-running the exact same scripts in the exact same environment. Or it could be more complex as giving someone a broad experiment/simulation, and hoping that person can figure it out without copy-pasting your code.

In the grand scheme of “good science”, your methods have to be correct. Before you take your technique to study some obscure, complex system, how about some sanity checks that your results work for something simple, like water? In general software engineering, unit tests are easier in that the inputs and outputs are simpler and more direct. In scientific software, it’s a little more complicated and groups can take a variety of approaches (checking input, doing energy calculations, checking if a simulation doens’t crash, etc.), but a systematic testing framework is necessary to ensure correctness and accuracy.

If you’re trying to popularize a method or software (AKA citations), it helps if external audiences can understand the codebase before they get flustered, give up, and go to the easier-to-implement method.

How do we start addressing technical debt?

There are bigger brains who have thought longer about the issue and have considered many external factors. I’ve had some chances to talk and pick their brains - it’s complicated. Broadly, this could be split into two categories: the small, growing code base vs. the large, archaic, software monolith

I should mention that the landscape of government funding is acknowledging the need for sustainable software and helping develop centers that can organize and facilitate sustainable efforts, like URSSI, MolSSI, Nanohub, among others

Easier: the small, growing code base

Like cleaning your room, it’s easier to clean your room daily or weekly before the mess is incomprehensibly large after a year of not cleaning. Refactoring often is very important. As the codebase grows, functions, routines, classes, modules, files may need to be re-organized into a cohesive package rather than just of a jumble of files that don’t seem to fit well together.

Write tests as you go. It feels less laborious if the tests are written as a new routine/module is put together. Depending on the scope of the project, unit tests, integration tests, regression testing, stress testing, etc. are all different sorts of tests to sanity-check and expose bugs.

MolSSI has a good cookiecutter for any package getting started, and it’s much better to start off on the right foot to set a pattern or set of practices before things get out of hand.

It’s important to establish best practices as early as possible, so good design and infrastructure can be in place for the future.

Harder: large software monoliths

In my experience, this is where a good portion of academic software stands. >10,000 lines of code with poor testing, organization, or modularity.

One approach involves a dedicated application support engineer on hand to refactor and maintain. (this job has many names, but essentially a somewhat permanent position for someone who is familiar with the code). Obviously this costs money, and the academic position is significantly less enticing than a corresponding role in industry (salary, culture, career growth). Some of the most successful software sells academic and commercial licenses, but that becomes a whole other beast to tackle in the open source community. Otherwise, you can hope you have a very charitable graduate student that spent his/her PhD with this package and you hope will donate time post-graduation to supporting the package. This is voluntary, so large code overhauls are unlikely. Honestly, this is voluntary, so expecting anything is optimistic, especially since PhD graduates can be burnt out.

Another approach involves accepting the monolith as it is, but trying to build around that with good practice. For example, if someone wanted to contribute a module/routine, make sure that routine is testable and sufficiently modular while still interacting well with the overarching package. This could take extra work if this involves making different programming languages work seamlessly well together. Another example, if you have an old simulation package, the simulation package itself might be hard to re-factor, but the mechanisms by which you generate inputs (coordinate files, simulation parameters) or analyze outputs (trajectories, energies) might be a more tractable project to raise to modern code standards.

Given the labs have sort of rooted traditions and work environments, instilling an ethos of sustainable software definitely takes a lot of initial work to foster these practices, but the open source community (and the molecular sciences sub-community) is friendly and willing to help.

Overall, I think this approach is a sort of a compromise between the hefty resources required for sustainable software and the long-term benefit of sustainable practices.

If there’s anything to take away from this

Sustainble software is essential to long-term productivity. Technical debt is going to hinder education, progress, and collaboration. If you’re a manager, boss, advisor, etc., it’s important to recognize these issues and try to develop a plan of action with your team and the ones who are heavily involved with the codebase.