Bayesian Methods and Molecular Modeling 1

Published:

(Last updated: 2019-07-31). This is an ongoing post as I work through a tutorial I found.

Introduction

Within the world of molecular modeling, a very exciting group is doing some interesting work. They are the OpenForceField consortium. Looking through one of their workshops, they draw some interesting analogies between developing force fields and bayesian inference. As someone transitioning from molecular modeling to data science, this is certainly an interesting intersection.

A big question

Given some thermodynamic/QM data, how can we best parametrize force fields?

Let’s step back a bit and make it sound more statistics-y.

Given some energetic data, how can we best model the energy of a system? What is the best distribution/equation to model the energy (aka force field)? And what are the best distributions to describe the parameters of the model? From these fitted/parametrized models, can we interpret anything from them? Can we sample/simulate anything from them?

Learning some Bayesian methods

Here’s where I stumble through miscellaneous talks, lectures, publications, and tutorials to try to piece together bits of this field. I found a particularly interesting tutorial by Chris Fonnesbeck

Important: I am really hoping someone out there is reading this and will correct me where I am wrong. I’ve learned solo-learning can be trial-and-error, and having external input can be very invaluable for guiding education.

Notebook 1: Introduction to PyMC3

Their example is studying radon levels (actually, log(radon)) in households, developing a model, and trying to identify how many households are greather than a threshold.

- We are interested in the posterior distribution given the data

- To develop a sampling distribution for the data, they use a normal distribution, which requires parameters for $\mu$ and $\sigma$, and also is based on an observed distribution (the gathered data)

- To develop a model or distribution for $\mu$, they first approximate/guess with a normal distribution (it’s okay if the log radon is negative)

- To develop a model or distribution for $\sigma$, they first approximate/guess with a uniform distribution (standard deviations and variances shouldn’t be negative)

In actuality, first the models for $\mu$ and $\sigma$ came first, THEN the sampling distribution for the data was built off the $\mu$ and $\sigma$ distributions in addition to the observed data

The overarching model was fit using a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method.

After fitting the model we can observe some probabilities about a point estimate, $\mu$:

- Probability that the mean level of radon is above a threshold

- Probability that the mean level of radon is below a threshold

Translation to molecular modeling

Our posterior distribution is the force field (potential energy function) given some observable. Analogously, this was the posterior distribution of radon levels given the observed data.

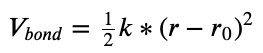

- In our molecular model, let’s say we just model the force field as harmonic springs

. Here, the two parameters are $k$ and $r_0$

. Here, the two parameters are $k$ and $r_0$ - In the radon model, we modeled with a normal distribution. There, the two parameters were $\mu$ and $\sigma$

- We used normal distributions for $\mu$ and $\sigma$. For $k$ and $r_0$, we know they should be non-negative (force constants and equilibrium lengths, respectively, are physically and generally non-negative), but we could use some sort of distribution that won’t get us negatives

At this point in both cases:

- We have an equation that expresses either our energy or the radon level (force field, posterior distribution).

- We have also identified the associated parameters in these equations ($k$ & $r_0$, $\mu$ & $\sigma$).

- For these parameters, we are estimating/approximating them via some other equation or distribution (normal or uniform)

The next step is to fit the model using some sort of sampling method. Molecular modelers would call this parametrization. In layman’s terms, I think this means some sophisticated guess-and-check or numerical optimization method to get the parameters that well-describe the observed data.

Now we have our parameters, so we can sample from this model or distribution (simulating, sampling), and see how well the simulated/sampled data recreates the generated data.

We can interpret these models: make some statements about the mean radon model or make some statements about the equilibrium bond length

Lastly, sensitivity analysis means messing with the underlying assumptions - what if we didn’t use normal/uniform distributions to describe [$k$, $r_0$] or [$\mu$, $\sigma$]? I think you could go one step further and mess with the underlying model, what if the radon level wasn’t modeled as a normal distribution? What if the force field wasn’t modeled as harmonic spring bonds?

I would hazard a guess and say not to try radically different models if they intuitively don’t really describe the data we are interested in modeling - modeling a force field (energy) as a purely random distribution would probably be a physically-unrealistic model and would not describe your data well.

Notebook 2: Markov chain Monte Carlo

(Update 7/31: Some of these early bits (from 7/30) are incorrect, and then I later correct myself - Jump to the 7/31 Update if you don’t care to see me be wrong).

This was a lot more than notebook 1. On a completely different note, there’s so many parallels to molecular modeling here, and I keep thinking of everything in terms of molecular modeling and I’m not sure if that’s hindering or facilitating my education. I’m going to unwind some thoughts here.

Once again, Bayesian methods are used to estimate parameters of a model. If your model is a normal distribution, your parameters are $\mu$ and $\sigma$. If your model is a line, your parameters are slope and intercept If your model is a harmonic spring, your parameters are force constant and equilibrium bond length.

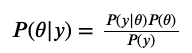

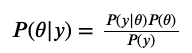

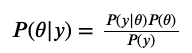

Bayes’ formula is used to estimate the probability of certain parameters given some observed data.

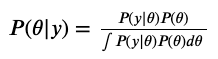

The denominator, $P(y)$ is called a normalization constant or marginal likelihood. Okay, well how do you calculate that?

To compute the marginal likelihood (probability of one variable), we have to compute this integral of the joint probability distribution (probabilities of two variables) along the other variable.

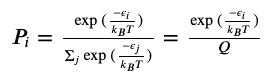

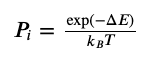

Here’s the first analogy to statistical mechanics:

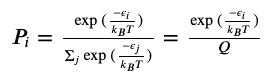

Where $\epsilon$ is the energy of state, $k_B$ is Boltzmann’s constant, $T$ is temperature, and $Q$ is our normalization constant (in fancy stat mech terms, this is the canonical partition function). Except this probably isn’t as noteworthy as it seems, since probabilities, in general, are just numbers of desired outcomes divided by all possible outcomes.

## (Ignore this is wrong) Back to Bayesian, this marginal likelihood integral is analytically hard to compute, so we have to use some numerical sampling methods. In molecular modeling, we are also trying to compute an integral over phase space (the 6N distribution over positions and velocities, but really just 3N positions because the velocity component is a priori known based on temperature). In both methods, we can employ Monte Carlo methods. In Bayesian, this is Markov chain Monte Carlo.

Side note: Monte Carlo integration

Let’s say you wanted to integrate $f(x)dx$. Assuming $f(x)$ is complicated and can’t be solved analytically, you use a numerical method like Riemann sums, Simpson’s Rule, Trapezoidal Rule, etc. The summary of these numerical methods is you (uniformly) pick a bunch of $x$, compute $f(x)$, and draw a bunch of rectangles whose height is $f(x)$ and length $x_{i+1} -x_i$ (otherwise known as $dx$), then sum up all those areas.

What if you didn’t pick $x$ uniformly? If you randomly picked $x$ (and adjusted the area summation to account for the non-uniform $dx$), you would be implementing a crude Monte Carlo integration.

To sum up Monte Carlo, pick random inputs, evaluate the function at those inputs, compute area, and sum.

Back to the notebook

Markov chains essentially mean that the probability of visiting a future state is dependent on what your current state, but not any other state in history. In the Monte Carlo scheme, this means, while you are “randomly” generating inputs, your next input is somewhat dependent on your current one.

Some of the underlying theory says you can use Bayes’ theorem (again, but applied to the Markov chain, not how we’re obtaining model parameters), to demonstrate a concept known as detailed balance that means you have balanced movement through phase space (this is a princple that holds for broader statistics in addition to molecular modeling Monte Carlo methods).

Okay, so if our next input depends on our current input, what is the critieria or algorithm we use to pick the next input in this integration scheme?

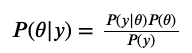

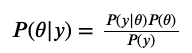

One algorithm is Metropolis-Hastings where you accept or reject based on the ratio of probabilities of new-input to current-input. This means comparing $P(\theta’)$ to $P(\theta)$, which I think means referencing our posterior distribution ($P\theta|y$).

In molecular modeling, we relate ratios to exponentials of energies so that our acceptance ratio simplifies to:

(7/30) Checkpoint: maybe summarizing things so far

- We want to model some sort of observable, which requires parameters

- We want to get the observable’s posterior distribution, which tells the probability distribution of certain parameters given the observable data

- We have Bayes’ theorem that formalizes some relationships

- We have the likelihood $P(y|\theta)$, which is an equation/distribution that depends on our parameters. From notebook1, this is a model/distribution we specify beforehand, with parameters we are trying to find.

- We have the prior $P(\theta)$, which is an equation/distribution of our parameters. From notebook1, this is a model/distribution we specify beforehand, with parameters we guessed.

(## ignore this is wrong )We have our marginal likelihood $P(y)$, which is re-written as an integral of $P(y|\theta)P(\theta)d\theta$, which is an integral of our likelihood and prior we just outlined.(## ignore this is wrong) To evaluate this integral, we use a Markov chain Monte Carlo method to pick different values of $\theta$, evaluate the product of likelihood and prior, then compute the summation. This integration method requires lots of iterations/sampling (this sampling is NOT sampling the observed data, but sampling different $\theta$ parameters).(## ignore)This integral is really difficult to comprehend in my opinion.(## ignore)You are computing an integral to end up with a posterior distribution(## ignore)But to compute the integral iteratively and numerically, you need to continuously re-evaluate the posterior distribution to choose moves based on Metropolis-Hastings.

(## ignore) How we efficiently calculate this integral is where the Bayesian inference methods get interesting from a computational perspective.

I think writing some of this out maybe helped my own understanding. Again, if someone out there is reading this and deems me incorrect, PLEASE contact me - I’d love to learn this properly. For now, I’m going to take a break and return to this notebook 2 later - we’re going to be hitting some crazy similarities to molecular simulation.

(7/31) Update: I was pretty wrong yesterday

Let me at least re-iterate what I still think is correct:

- We want to model some sort of observable, which requires parameters

- We want to get the observable’s posterior distribution, which tells the probability distribution of certain parameters given the observable data

- We have Bayes’ theorem that formalizes some relationships

- We have the likelihood $P(y|\theta)$, which is an equation/distribution that depends on our parameters. From notebook1, this is a model/distribution we specify beforehand, with parameters we are trying to find.

- We have the prior $P(\theta)$, which is an equation/distribution of our parameters. From notebook1, this is a model/distribution we specify beforehand, with parameters we guessed.

- We have our marginal likelihood $P(y)$, which is re-written as an integral of $P(y|\theta)P(\theta)d\theta$, which is an integral of our likelihood and prior we just outlined.

- It’s important to remember this is just a (normalizing) constant, as in, this number doesn’t change.

What is the point of the Markov chain Monte Carlo then?

We are trying to sample a bunch of different parameters $\theta$, and a Monte Carlo approach works to sample parameters, with a Markov chain being an efficient way to sample randomly while keeping track of your current state.

I had to work backwards, reverse-engineer, dissect the code (whatever you want to call it).

calc_posterior

calc_posterior is a method to calculate the joint posterior, given your data: measured output (recorded prices) + measured input (recorded ages) and your sampled parameters (slope, intercept, stdev of the posterior distribution assuming it obeys a normal distribution). It’s worth mentioning that we are working in log terms, which means products of values become summations of log(values).

So let’s pull up Bayes’ theorem again, but focus on the numerator  . We are only interested in the likelihood and the prior. To calculate the log posterior, let’s first compute the prior $P(\theta)$. Because we have 3 parameters, we have 3 prior distributions to look at. Remember, a priori we make some claims about the distributions of these parameters. We said the slope and intercept obey a normal distribution (in the example, the center was on 0 with standard deviation 10000). Within this function, we have an estimate for the slope and intercept. Given the specified (normal) distributions, we can compute the probability of observing the slope, and we can compute the probability of observing the intercept. Multiplying probabilities is adding the log probabilities. The third parameter, t or $\tau$, pertains to a standard deviation (actually I think it’s the variance but they allude to the same thing). Given that $\tau$ has to be positive, we claimed its distribution obeyed a gamma distribution. So given the specified (gamma) distribution, we can compute the probability of observing this $\tau$, and add this to the log posterior. At this point, we have accounted for all 3 priors.

. We are only interested in the likelihood and the prior. To calculate the log posterior, let’s first compute the prior $P(\theta)$. Because we have 3 parameters, we have 3 prior distributions to look at. Remember, a priori we make some claims about the distributions of these parameters. We said the slope and intercept obey a normal distribution (in the example, the center was on 0 with standard deviation 10000). Within this function, we have an estimate for the slope and intercept. Given the specified (normal) distributions, we can compute the probability of observing the slope, and we can compute the probability of observing the intercept. Multiplying probabilities is adding the log probabilities. The third parameter, t or $\tau$, pertains to a standard deviation (actually I think it’s the variance but they allude to the same thing). Given that $\tau$ has to be positive, we claimed its distribution obeyed a gamma distribution. So given the specified (gamma) distribution, we can compute the probability of observing this $\tau$, and add this to the log posterior. At this point, we have accounted for all 3 priors.

Next, we look at the likelihood, $P(y|\theta)$. This component is different because now we have to look at our observed data, which is 39 data points of (age, price). It’s wrapped in nice vectorized calculations, which means a single line of code acting on a variable actually acts on a bunch of values. In this scope where we are calculating the posterior, I reiterate: we have estimates for 3 parameters. We can use these parameters and our model to try to predict some output (price) given the actual input (age). In this example, we are modeling the relationship between price and age with a linear model. We have a guess for the slope and a guess for the intercept. For all of our 39 ages, let’s use these 2 parameters and model (slope, intercept, linear equation) to predict 39 prices. In the code, this is mu = a + b*x, where x is our array of ages. Now we have 39 predicted prices and 39 actual prices. Let’s return to the likelihood $P(y|\theta)$, the probability of the observed data given your parameters. The hidden middle step is the underlying model that converts parameters + input into output, which is why we compute mu. Examine the next line of code logp += sum(dnorm(y, mu, t**-0.5)). In particular dnorm(y, mu, t**-0.5), in which we compute the probability of observing the actual, observed price under/given a normal distribution centered around mu with standard deviation $\tau$ (this is where the 3rd parameter comes in!). And then we sum up all these log probabilities for all 39 data.

Compare and contrast the code/function calls, i boiled them down for simplicity:

- Priors :

logp = dnorm(a,0,10000) - Likelihood:

logp = dnorm(y, mu, t**-0.5)

With the prior, we knew the underlying (normal or gamma) distribution and parameters of that distribution (center and stdev), and those were hard-coded/fixed/constant. The only variable/thing that changes is our estimate for the parameter, and then we compute the probability of observing that parameter under a (fixed) distribution.

With the likelihood, we have many more variables that will change throughout the sampling. Each iteration, we are coming up with a new distribution (based on mu and t), and computing the probability of observing the price (whicch is our observed data) under this new distribution. To come up with this new distribution, we still made a claim that it was a normal distribution, but the center (mu) and variance (t) of the normal distribution are subject to change. t or $\tau$ is one of the 3 parameters we are continuously changing/sampling, so that one comes sort of “free” in this iterative process. mu, however, is our price, thing we are trying to predict. mu isn’t free, we have to compute mu based on our model and other parameters (slope and intercept). But at least y is free, it’s the observed data (price) that we measured.

Let’s rephrase this another way

- You want a model to relate input to output. It is some sort of mathematical function/equation that adds/multiplies/exponentiates/logs your input to get an output. You have observed data for (input, output)

- You need parameters for this model. These are not observed and you have to come up with them. We make a claim about the distribution of these parameters (they seem normally distributed about 0 with standard deviation 10000). In the parentheses, we have just specified 3 pieces of information - the type of distribution, and the 2 parameters of that distribution. These distributions compose your prior

- Using Bayes’ theorem, we are trying to identify the parameters for the observed data according to our model. This manifests as the posterior distribution, the probability of a particular value of a parameters given the observed data. This means we say “hey here’s a range of possible parameters of the model, and here’s how likely each of those parameters seems, given the data we have gathered”. We aren’t making a definitive claim on what the parameters are, just providing some possible parameters and likelihoods.

- We have just discussed the posterior distribution and prior, now we have to address the likelihood. This is the probability of the observed data given your parameters. We make a claim about the distribution of the data (it seems normally distributed). Unlike the prior, we have only specified one piece of information, the type of distribution.

- What’s important to note is that the properties of the distribution (center and stdev) are computed over the course of the MCMC simulation.

- The nature of this likelihood distribution changes over MCMC, whereas the nature of the prior distribution does not change. Over the MCMC, we get new parameters.

- In the case of one observed datapoint: For the new parameters, we re-predict the price from the age. The predicted price forms one property of our normal distribution (center), and this predicted price arises from our underlying model (the linear function)! But the other property of our normal distribution (stdev), is another parameter we are continually updating (like the slope and intercept).

- Within this new, updated distribution (which depends on our model and parameters), we look at the probability of observing the datapoint. Do this for all datapoints.

- I find the likelihood component complicated (I mean, I got it wrong the first time around, and probably got it wrong in this explanation), so I put a lot of words there.

What is the role of MCMC? What is the role of the marginal likelihood?

The whole point of MCMC is to try a bunch of different $\theta$ and get the probability of that $\theta$ given our data - sample different $\theta$ to build our posterior distribution.

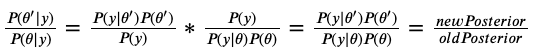

One element of MCMC is the use of an acceptance criteria to accept or reject proposed, new parameters (Metropolis-Hastings). This notebook2 used some different notation, but I think the code explains more. alpha = proposed_log_prob - current_log_prob, we are looking at the log-difference of the posterior distributions (which is the non-log-quotient of the posterior distributions).

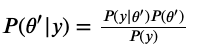

Here’s some math proof, where $\theta$ is the current $\theta$, and $\theta’$ is the proposed $\theta$ that we accept/reject.

The marginal likelihood $P(y)$, being a constant, cancels out in the division!

To summarize the MCMC loop and sub-routines:

- Propose a model to relate price and age (linear model)

- For the model, propose distributions (and properties) for the parameters we are trying to find (prior)

- For the model, propose a distribution (and properties) for the resultant output/data (likelihood).

- Note that THIS distribution will be centered on the predicted output, with variance as a parameter we are trying to find.

- Propose an initial guess for the parameters (slope and intercept of model, variance of the likelihood)

- Now we begin the MCMC loops

- Propose new $\theta$ values (slope, intercept, variance) according to the prior distributions we had already specified

- With the new $\theta$, compute the new posterior

- Find the probability of observing these $\theta$ according to their prior distributions

- With the model and new $\theta$, predict some data (prices) given our measured input (ages)

- With our likelihood distribution centered around each predicted value (and variance being one component of the new $\theta$), find the probability of observing the actual, observed value.

- Sum up the logs (of the priors, of the likelihood of each actual observed value) , this is your new posterior

- Calculate the acceptance ratio: compare the new posterior and the old posterior. Marginal likelihood $P(y)$ is cancelled out, so we can ignore it.

- Compare the acceptance ratio to a value from a random, uniform distribution.

- If the acceptance ratio is greater than the random number, accept the proposed parameters and move onto next iteration with proposed parameters

- If not, reject the proposed parameters and move onto the next iteration with the same/old parameters

- Do this a bunch of times: you are trying different $\theta$ and checking how well it fits/models the data

- At the end of the day, you will have just a huge collection of attempted $\theta$.

- If well-sampled, the commonly-visited-$\theta$ are the $\theta$ most likely to explain your observed data (histogram $\theta$ for a good visualization).

I think that summarizes my learning of Bayesian methods up until now. This next section, still in notebook2, deals with the sampling method (how we choose $\theta$. In this 7/31 section, I didn’t really mention molecular modeling, but now I probably will.

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo

Some $\theta$ are more typical and likely (we want to sample these), where as other $\theta$ are less likely (less important to sample these). In molecular simulation, some configurations (sets of coordinates) are more likely than others. We are generally interested in the more probable configurations.

To include Hamiltonian properties, we are characterizing $\theta$ using potential and kinetic energies - the former depends on “position” and the latter depends on “velocity”. Our $\theta$ can be considered a particle who can be characterized using its position and velocity - potential and kinetic energy. Some say velocity, others say momentum, but they are very tightly related via mass, except mass isn’t super important for these HMC methods.

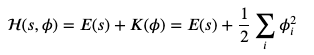

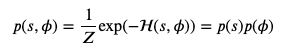

In a canonical distribution, probabilities are proportional to the exponential of their energy (Hamiltonian), the Hamiltonian is expressed a sum of potential and kinetic energies

Where $s$ is our position, $\phi$ is our velocity. Physicists and molecular modelers will probably cringe that we aren’t using $r$ and $v$ or $r$ and $p$. Remember that kinetic energy is $1/2 * mv ** 2$, but mass is 1 in these Bayesian methods.

And the associated probabilities of each state (a state is a collection positions and velocities):

Now this very well matches canonical distribution as applied to statistical mechanics:

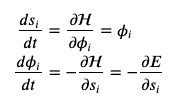

Physics says we can relate position, energy, and the Hamiltonian via some differential equations (with respect to time), and we apply them to Hamiltonian dynamics for this Bayesian sampling.

The top line, the derivative of position WRT time is the velocity (fundamental), which is also the derivative of the Hamiltonian WRT velocity (analytically differentiate the Hamiltonian yourself, observing that potential energy is a constant WRT velocity).

The bottom line, the derivative of velocity WRT time is acceleration (fundamental), which is also the negative derivative of the Hamiltonian (energy) WRT position - in molecular modeling the derivativative of energy WRT position is our force.

At this point, we have some coupled, partial differential equations. All molecular modelers are familiar with this - we just need to numerically integrate these PDEs over time to get a trajectory of positions and velocities! There are a whole slew of integrators in Hamiltonian Dynamics as there are in Molecular Dynamics, and the same considerations for these integrators both hold. The notebook2 uses leap-frog integration, which is actually a popular integration method in MD. I’ll just note that coding up some of these integrators is a pain because you are taking a mixture of full, half, etc. steps and evaluating velocities/forces at different steps, until you actually take a full step to move to the next iteration/timestep.

In this Bayesian sampling, now that we have a Hamiltonian, the MCMC loop changes a bit - do some Hamiltonian Dynamics steps to get a new state (set of positions and velocities), then choose whether or not you want to accept these steps to get to a new state, via the same Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. While the velocity is artificial in the sampling, the position is analogous to your $\theta$

In molecular simulation, people call this MCMD, where you do a bunch of MD steps to get a new state, and then you use MC methods to choose to accept this new state or not.

Now here’s where the molecular modelers might finally have a leg-up, and that’s in enhanced sampling (some call this non-Boltzman sampling because you are no longer sampling according to the Boltzmann distribution). Basically you introduce extra forces/energy and bias your trajectory/system/ positions away from already-visited states.

Bayesian-ists have a variety of enhancing sampling, but it seems they also echo similarly to molecular simulation enhanced sampling.

The thing with these methods, you are artificially changing the frequency/histogram with which you visit states, so you need a way to re-weight the biased/artificial histogram to recover the true histogram/distribution (I’m speaking from molecular modeling experience, but I’m guessing Bayesian stats requires something similar)

This concludes my study of Notebook2. Call me out if I got anything wrong, please.